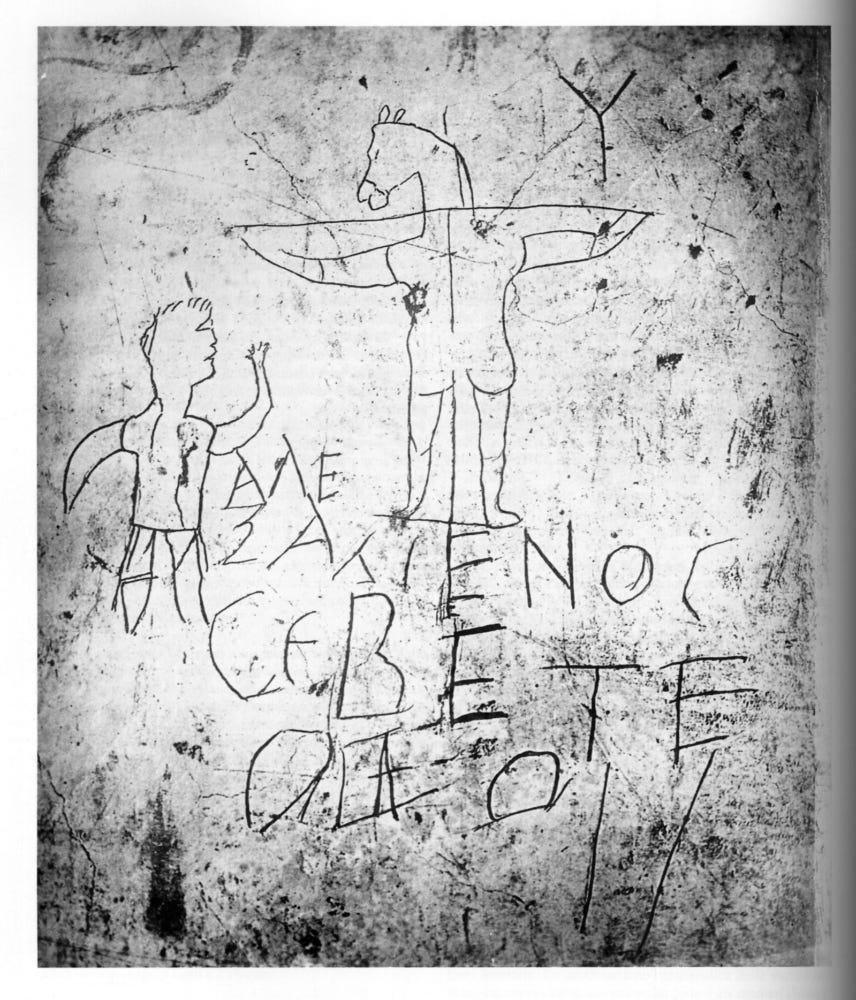

Chapter 3, "Esper" / Alexamenos

How an 1800-year-old Anti-Christian Graffiti in Rome Can Teach us about Jesus and What it Means to Follow Him

“Clamped high on the wall in the corner of the gallery, it seemingly is a blank slab, the lines of the original image almost invisible. To be discernible at all, the photograph must be enhanced.”

James Grout, Encyclopaedia Romana[1]

“Enhance 224 to 176. Enhance, stop. Move in, stop. Pull out, track right, stop.”

Rick Deckard to the Esper Machine, “Blade Runner” (1982)

I am a devotee of the great 1982 cult classic sci-fi film, “Blade Runner.” “Blade Runner” is the cinematic rendering of Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, though it is likely the case that more people know the story through Ridley Scott’s moving depiction on the screen than through Dick’s story.

It is the future. 2019 in fact. A detective named Rick Deckard is, against his wishes, pressed back into service in the LAPD Bladerunner unit: a unit of specially trained police who hunt down and “retire” (read, “kill”) humanoid robots called “replicants.”

Deckard, memorably played by Harrison Ford in the film, enters the apartment of a replicant named Leon. In a bureau in the apartment, Deckard finds some of Leon’s photographs. Deckard takes them with him back to his own apartment. After getting a drink, Deckard sits before the Esper machine, a smallish-looking computer system. He takes one photograph from the stack he took earlier—a seemingly unremarkable picture of the inside of an apartment—and feeds it into a slot in the Esper machine. The screen lights up with the scanned image of the photograph.

Now, Deckard begins to speak. Those who have seen the movie will remember the scene: Deckard’s weary gaze at the Esper monitor, his monotone instructions to the machine, and the clicking, beeping, shuttering sounds of the Esper as it explores the photograph under Deckard’s verbal commands.

Enhance 224 to 176. Enhance, stop. Move in, stop. Pull out, track right, stop. Center in, pull back. Stop. Track 45 right. Stop. Center and stop. Enhance 34 to 36. Pan right and pull back. Stop. Enhance 34 to 46. Pull back. Wait a minute, go right, stop. Enhance 57 to 19. Track 45 left. Stop. Enhance 15 to 23. Give me a hard copy right there.

The Esper machine responds throughout to Deckard’s commands. As the Esper examines the picture, here closer and there from further out—panning out, moving in, drawing back—something surprising happens. Deckard has the machine center and stop on a round mirror in the photograph before zooming in on one area of its reflection. At this point, we are zooming in on the part of the apartment reflected in the mirror. We are, in a sense, beginning to move around inside the image of the apartment. But then, as Deckard has the Esper pull back, enhance, and “track 45 left” on the reflected image, we somehow see behind an object in the apartment to a previously-hidden woman asleep in a part of the apartment to that point inaccessible in the photograph. That lady will turn out to be the replicant Zhora, with whom Deckard will soon have a most violent encounter.

The Esper machine was able to take Deckard into the image where he discovered what lay deeper within. He was able to get behind images within the image to learn more about the depths and complexities of the world of the photograph.

It is a memorable scene, and it raises a most interesting question (and one that has been debated on sci-fi chat boards online): How can the Esper machine essentially take us into the image to see things that are, at first glance, hidden? Is the image somehow a special 3-D image? (It does not appear to be.) Or, as one commentator suggests, is the photograph more like a GIF than a mere photograph? Or is the Esper machine just that good?

It is fun sci-fi grist for the mill, the Esper machine. Yet, the question of Leon’s picture is also the question of the Alexamenos Graffito: Can we really enter into the hidden world of a picture, an image, into what lies behind what we initially see on the surface? How can we? If so, how far can we go?

Oliver Larry Yarbrough believes that the Alexamenos Graffito has depths to be mined. He writes:

Thus, though crudely drawn, the graffito should not be seen as simple or naïve. Indeed, there are numerous levels of meaning to it and the whole piece works because the artist combined image and word so evocatively and so precisely.[2]

If we feed the Alexamenos Graffito into the Esper machine, what might we find? What realities lie behind the image we see? This, in part, is the journey of this book.

Why on Earth?: The World behind the Image

In 2016, the late historian Larry Hurtado delivered the Père Marquette Lecture in Theology at Marquette University. He published that lecture in a small book with an intriguing title: Why on Earth did Anyone Become a Christian in the First Three Centuries? The title itself situates Hurtado’s question and proposed answer squarely in the world of the Alexamenos Graffito, since it can reasonably be dated to the late-2nd/early-3rd century. As such, it helps us understand the social, political, and theological realities that are hiding behind our initial look at this image.

The research of Hurtado and other historians allows us an Esper possibility with Alexamenos: the chance to enter into the picture and move around a bit in its world.

It has become seemingly commonplace for people to point out that the Sunday School version of early church history in which Christians the empire over were constantly and in every place being thrown to lions is a bit off the mark. There were indeed periods of persecution, but the intensity and extent of these varied over the years.

What Larry Hurtado has demonstrated so well in his Père Marquette Lecture is that there were lots of ways the lives of Christians were made difficult and unpleasant that fall short of being thrown to the proverbial lions. Hurtado argues and demonstrates that “more commonly…early Christians were the objects of ridicule and harassment, and even physical abuse by family members and wider social circles.”[3]

This is helpful. It creates a spectrum of unpleasantness, if you will, that helps us understand early Christian experience in more nuanced terms. Alexamenos’ experience likely falls in this “objects of ridicule and harassment” category.

Hurtado makes an interesting and, as far as the Alexamenos Graffito is concerned, telling point about Christian devotion in particular during this time.

Indeed, it is probably the case that the social costs of becoming a Christian were exceptional in comparison with any other kind of voluntary religious choice of the time. In any other religious group in the ancient world this had no necessary effect upon your other religious duties or choices. You retained your ancestral deities and rites, and, indeed, could join more than one voluntary religious group without any sense of offense against any of the deities involved. But for Christian converts to observe conscientiously the demands that their faith laid upon them meant an exclusivist stance, abstaining from the worship of all deities other than the one God and Jesus. This had far-reaching implications for a Christian’s social existence.[4]

Hurtado points to the words of Lucian of Samosata from the late-2nd century (and so possibly roughly contemporary to Alexamenos) about Christians.

The poor wretches have convinced themselves, first and foremost, that they are going to be immortal and live for all time, in consequence of which they despise death and even willingly give themselves into custody, most of them. Furthermore, their first lawgiver [Jesus] persuaded them that they are all brothers of one another after they have transgressed once for all by denying the Greek gods and by worshipping that crucified sophist himself and living under his laws.[5]

No, it is likely not the case that every Roman wanted to throw every Christian to lions. But it is certainly fair to say that the heart of the Christian message butted heads with dominant Roman society and belief systems in a way that many Romans found irksome or odious, leading to reactions that many Christians found unpleasant and frightening. And the major agitations seemed to center around the Christian rejection of all other gods, the Christian belief in resurrection, the Christian exaltation of Jesus and his shockingly counter-culture message, and, to the Romans, the most shocking aspect of all: the Christian belief that the crucifixion of Jesus was anything other than something to be turned away from in disgust. Instead, the early Christians saw the cross of Christ as bound up with their own spiritual and even social liberation and eternal salvation.

Can you hear the Esper machine clicking and whirring as we move around and behind our graffito?

Enhance 224 to 176. Enhance, stop. Move in, stop. Pull out, track right, stop. Center in, pull back. Stop.

That which lies behind it and is yet embedded within it is coming more and more into view, and it is this: a culture in which the young Christian movement is seen as, at best, an odd eccentricity or a weird cult, or, at worse, a politically, socially, and spiritually dangerous group of duped malcontents. Perhaps they should not all be killed, these strange Jesus-followers, but it was hard for a Roman to imagine why they should not, at the least, be the butt of a good joke.

When Paul stood before Porcius Festus, the Roman procurator of Judea, in Acts 26, and spoke of the gospel of Jesus, Festus’ “loud” response was likely indicative of how the average Roman thought of these Christians: “Paul, you are out of your mind; your great learning is driving you out of your mind” (v.24). That is, the average Roman likely thought that the average Christian was, to be frank, a bit bonkers.

As Hurtado aptly summarizes:

Certainly, it appears that those with aspirations of social acceptance would have found being a Christian a distinct disadvantage…If what you desired was greater social acceptance, early Christianity was hardly a sensible route to take![6]

Foretold and Expected

Nor should the early followers of Jesus have found this social tension surprising, as unwelcome as it surely was. For Jesus Himself had said near the beginning of His Sermon on the Mount:

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are you when others revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so they persecuted the prophets who were before you. (Matthew 5:10–12)

And Jesus, too, knew what it was to be laughed at by an incredulous populace. Consider His healing of the ruler’s daughter in Matthew 9.

And when Jesus came to the ruler's house and saw the flute players and the crowd making a commotion, he said, “Go away, for the girl is not dead but sleeping.” And they laughed at him. (v.23–24)

To many people, being laughed at, being the butt of a pointed joke, is more painful than being slapped. In general, martyrs are seen by their killers to be at least dangerous and so worth killing. But to be made the object of a joke is to be dismissed as something not even worthy of the gallows.

So, too, the anguish of being socially ostracized can be acute. Peter, in 1 Peter 4:3–4, spoke of this dynamic when he wrote:

For the time that is past suffices for doing what the Gentiles want to do, living in sensuality, passions, drunkenness, orgies, drinking parties, and lawless idolatry. With respect to this they are surprised when you do not join them in the same flood of debauchery, and they malign you

These “Gentiles,” we are told, are “surprised when you do not join them in the same flood of debauchery.” So, they “malign” the believer who will not go along with their revelries. Becoming a social pariah is no pleasant matter, and the loneliness of these moments of reviling are hard to endure. I suspect there are those reading these words who would agree and who might even have scars of memory to prove it.

Alexamenos was laughed at. He was made an object of scorn. At least in the moment of the unveiling of this graffiti, he must have felt very alone.

To be sure, we have no reason to think that at least some of his fellow students gave him a good-natured elbowing or tousling of the hair accompanied with an “Oh, come on Alex! We’re just funnin’!” At least we may hope that this was the reaction. What else happened to Alexamenos? Antje Jackelén writes:

We do not know what became of him, if he still had any friends after this graffiti, or how his congregation supported him. Maybe he became isolated, even from his own people—you never know, there is probably something wrong with him when things have gone so far. No smoke without a fire! Rumors and opinions begin to live their own life, in the Roman forum as well as on Facebook and Twitter. Evil rumors and unfounded opinions are fertilized by thoughtlessness, laissez-faire, yes-men and -women, and by the far-too-widespread view that it is bad manners to become involved.[7]

Whatever else happened, the graffitist’s point was made. And the point was clear.

There was something very strange about these people called Christians, something that agitated, to greater or lesser extent, those shaped by the dominant culture of the time.

And this tension is what lies behind our graffiti.

Enhance 224 to 176. Enhance, stop. Move in, stop. Pull out, track right, stop. Center in, pull back. Stop. Wait a minute, go right, stop. Enhance 57 to 19. Track 45 left. Stop. Enhance 15 to 23. Give me a hard copy right there.

[1] https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/

[2] Yarbrough, Larry Oliver. “The Shadow of an Ass.” Text, Image and Christians in the Graeco-Roman World. Princeton Theological Monograph Series. Edited by Aliou Cessé Niang and Carolyn Osiek. (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2012) 244.

[3] Hurtado, Larry. Why on Earth Did Anyone Become a Christian in the First Three Centuries?. (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 2016) 9–10.

[4] Ibid., 14.

[5] Ibid., 71–72.

[6] Ibid., 106, 113.

[7] Jackelén, Antje. God is Greater. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2011) 17–18.