Chapter 4, "Imaginings, Part I" / Alexamenos

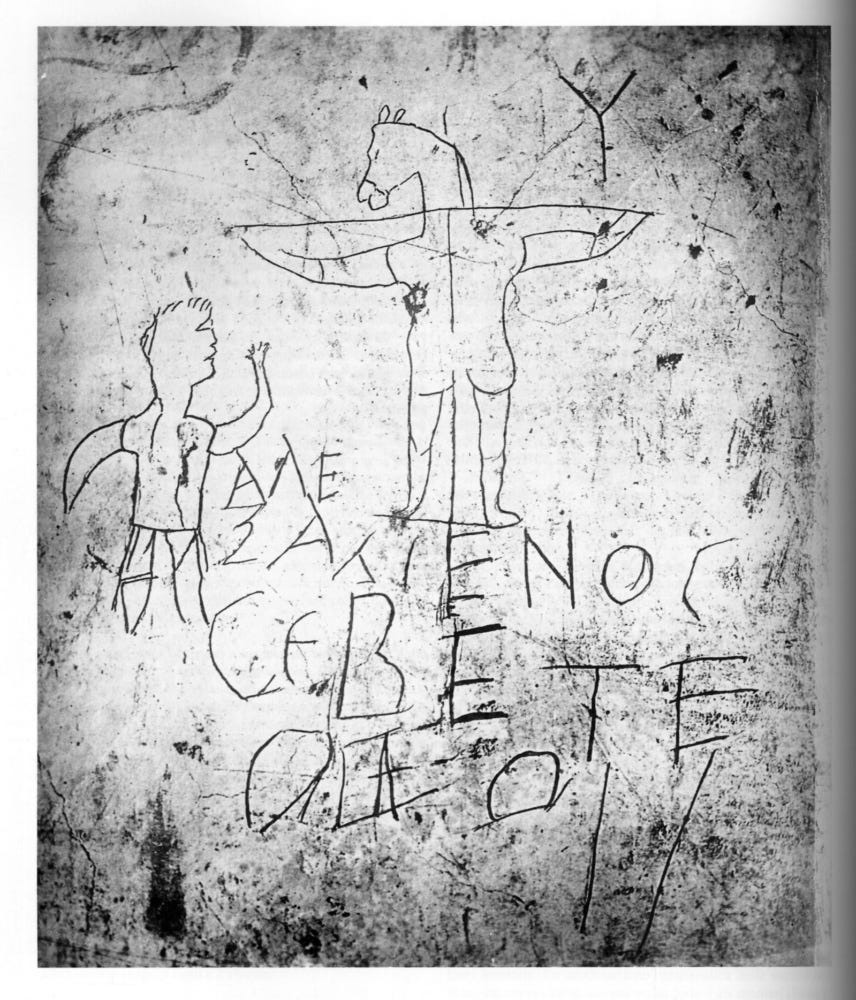

How an 1800-year-old Anti-Christian Graffiti in Rome Can Teach us about Jesus and What it Means to Follow Him

Since its rediscovery in the mid-19th century, there have been those who attempted to fill in, imaginatively, the gaps in Alexamenos’ story. Those creative imaginings appear throughout this volume. There is value in considering these. They demonstrate the different ways that the graffiti has hit the eye and ear and soul of people over the years. They solidify the staying power of the graffiti and the story behind it that we so badly want to know. They also demonstrate the inevitable limitations of our knowledge. Furthermore, they show how Alexamenos and the graffiti in which he is depicted has been viewed as an invitation not only to the workings of the imagination but to devotional inspiration as well.

In 1885, Parish Magazine, a publication of St. Andrew’s Church in Headington, England, included a short description of the discovery of the Alexamenos Graffito along with an accompanying drawing, both by “A.R.,” presumably the author and the artist.[1]

The announcement of the finding reports that those who discovered the graffiti supposed that the rooms of the paedagogium “had served as guard-rooms for the soldiers of the Praetorian guard, a body of troops retained for the especial protection of the Emperor and the city of Rome.”[2] The graffiti, we are told, “was evidently meant for the caricature of a Christian, of whom the Pagans believed the most absurd stories during the first three centuries.”[3] It postulates that Alexamenos was Greek, “but it does not follow that the man who drew the caricature of him was one…”[4] What is more, the announcement asserts:

In the second century Christians were numerous in the armies of Rome, as we know by some famous stories; and it may have been that Alexamenos was a Christian soldier in the Praetorian guard, who was taunted with his faith by his Pagan companions, one of whom endeavoured to cast ridicule on both his religion and himself by this rude caricature: a method of throwing discredit on sacred things and forms of belief unhappily not known in our own day.[5]

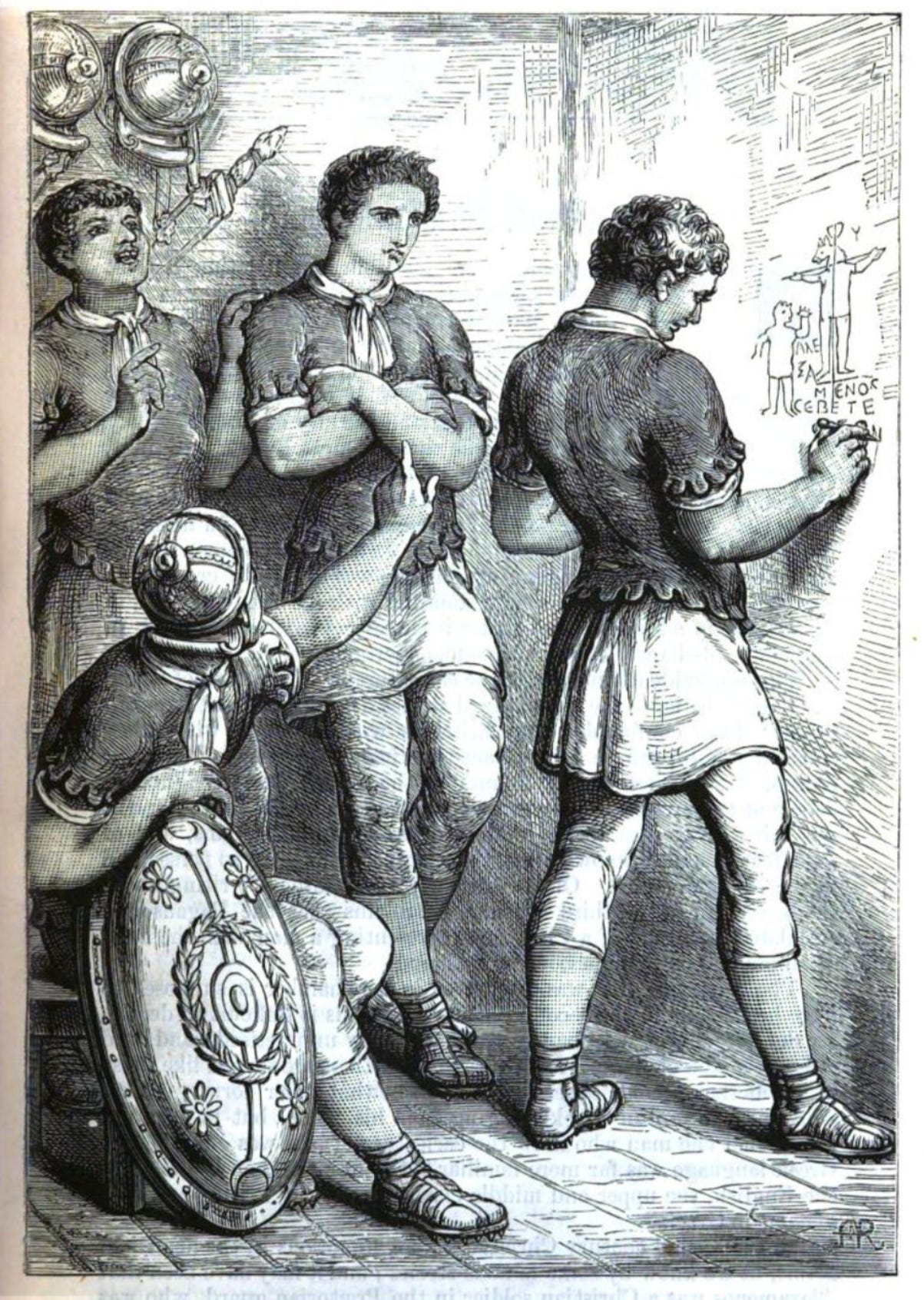

While there is some creative reconstruction in this description, it is in the accompanying drawing that “A.R.” gives fullest expression to his own imaginative rendering of what happened in that room when the Alexamenos Graffiti was scratched into the wall.

In the image, four young praetorian guardsmen—or, perhaps, four young men training for the guard—are present. One—the tallest of the four, handsome, strong, arms crossed—is leaning against the back-most wall. This is Alexamenos. He is watching another young man etch the graffiti into the wall. The graffitist is almost finished with his satire. We see the cross, Christ (donkey-headed), Alexamenos (hand upraised), and two of the three words that comprise the inscription. The young man rendering the drawing seems to be putting the final letter on “Theon” ([his] God). The “artist” is proud of his work, a sly smile on his face, his head down-bent, focused on his mocking masterpiece.

The other two young men are, to some extent, engaging Alexamenos. The one just to his right is laughing, head back, his left hand resting on Alexamenos’ right shoulder, his right hand pointing to the graffiti. The young man in the foreground is seated, his right arm on a Roman shield, his head turned away from the viewer and looking up at Alexamenos, his left arm extended forward and his index finger pointing at Alexamenos. We cannot see his face, but we can reasonably ascertain that he, too, is laughing.

Most telling is Alexamenos’ expression. His head is bent slightly forward. He is pensive, a veil of sadness on his face, his eyebrows (perhaps) slightly raised with a look of something like resignation. He is watching the scene unfold, receiving, absorbing the taunts of his friends. Tellingly, his eyes are on the graffiti, possibly on the crucified figure. He seems not to be looking with anger at the artist. He seems to be looking with acceptance at the cross itself, at the finalization of the mocking inscription. Perhaps he is looking at the image of himself: Alexamenos watching Alexamenos watch Jesus!

One does not gather that Alexamenos is in danger here. One gathers that he is simply the butt of a joke intended to mock and likely even to wound. It is a scene that might be repeated in a thousand locker rooms in any high school in America: young men razzing a young man. It is the kind of thing that anti-bullying efforts in school would seek to undo in our day.

In this image, a young man’s religion is mocked, and so the young man himself is mocked. So, too, the object of the young man’s attention: the crucified figure, mocked with the head of a donkey.

Modern categories do not come into play here. There is no polished ecumenism at play here, no interreligious dialogue, no “Coexist” bumper stickers. Here, a dominant system—Rome—vents its spleen toward a strange, foreign religious system.

The picture tempts us to say, “Boys will be boys.” And, indeed, they often will be. But the picture represents the clash of worldviews, a collision of theologies even. There is much more happening here than just these four boys. This is a clash of creeds: the gods vs. the crucified God, Rome vs. the Kingdom, Caesar vs. Christ.

In the room depicted here, the world at large is shown: the many who do not believe and the few who do.

As with Alexamenos in Rome, so, too, with Paul in Athens.

32 Now when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked. But others said, “We will hear you again about this.” 33 So Paul went out from their midst. 34 But some men joined him and believed, among whom also were Dionysius the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris and others with them.

“Some mocked. But others…”

This image by “A.R.,” this graffiti.

The laughing boys.

Alexamenos alone in their midst.

In the drawing, Alexamenos stares at the graffiti.

He is not laughing.

He is not enjoying this.

But neither is he despairing.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. (Matthew 5:10)

He looks at his crucified God—his arm crossed in confidence, not drooping in despondency—he looks at his crucified God…and he seems to understand.

[1] A.R. “Alexamenos, The Christian.” Parish Magazine. Edited by J. Erskine Clarke. XXVII (London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., 1885) 5–5.3

[2] Ibid, 5–2.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 5–2, 5–3.

Some thoughts don't change, they just update with the times.