Chapter 9, "Adoratio" / Alexamenos

How an 1800-year-old Anti-Christian Graffiti in Rome Can Teach us about Jesus and What it Means to Follow Him

In worshiping we bring the right hand to the kiss and turn the whole body round, which the more religious Gauls believe they did to the left.

Pliny, Natural History, 77 AD

I don't want to be doomed to mediocrity in my feeling for Christ. I want to feel. I want to love.

Flannery O’Connor, A Prayer Journal[1]

My father is a hardware salesman in South Carolina. He has been in and out of hardware stores in the eastern half of South Carolina my entire life. And, throughout my life, he has passed along the stories he has heard in these places and the events he has witnessed.

Once, shortly after the Jesus People movement swept east from California to the east coast, my father was in a hardware store talking to the store owner. A young man worked at the store, a young believer who had been influenced by the Jesus People movement. At some point during my father’s visit, this young man turned to the owner standing behind the counter and held one index finger in the air. This was the famous “One Way” sign of the Jesus People, a symbolic representation of John 14:6 and the truth of Jesus as the one way. Something prompted him to do this. This raised finger was intended to communicate the supremacy of Jesus Christ and to point all people to Him. It was an act of devotion, an act of adoratio, adoration.

The hardware store owner (the odds are, a traditional church goer grown weary with this modern and youthful incursion into the forms and rituals of the Christianity he preferred) grew irritated at the sign. “Oh good grief, stop that,” he said. In this way, the generational clash (likely) within the evangelical church of the Bible belt reared its head in the marketplace of the South.

Gestures can incite. Gestures can irritate. Gestures can inspire. Gestures can enrage.

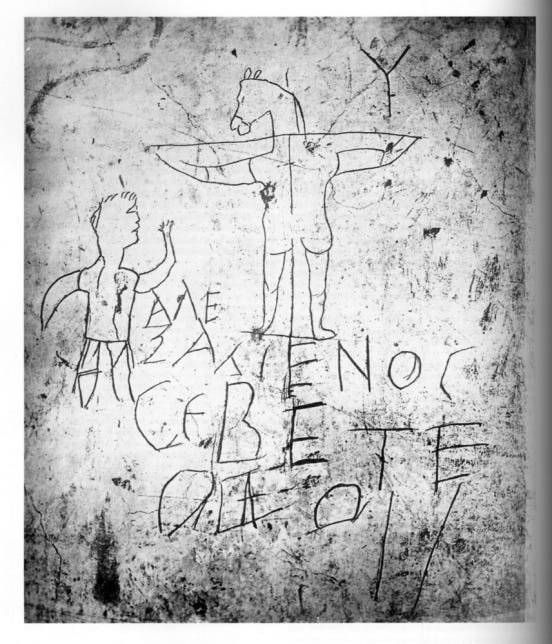

Alexamenos, our young Christian, raises a hand in worship to Jesus, his fingers splayed. Is it his right hand or his left hand? To me it appears to me that Alexamenos is facing the viewer with his left hand raised and his right arm behind him. Others contend, however, that this is a mistake. We are seeing Alexamenos’ back in the drawing, they assert.[2] If this is so, Alexamenos is throwing his right hand up with his left arm behind him.

What seems clear is that the depicted hand is intended to (1) show Alexamenos in a posture of worship and (2) mock this worship.

Gestures had meaning for the Romans, just as they do for us.

Robert Turcan has written of the specificity that accompanied religious gesturing in the Graeco-Roman world.

The gestures accompanying the word were just as rigorously codified. The cup for libations was not to be held, or the contents poured, in the same way for a god from on high and a god from the underworld. When sacrificing by the devotion “naming Tellus, one touches the ground; naming Jupiter, one raises one’s hands to the sky; making the vow, one touches one’s breast with both hands”…The deity is greeted by raising the right hand to the lips, as a sign of adoratio…[3]

Presumably, this is what Alexamenos is doing in the graffiti. Essentially, throwing a kiss, which, as Cyprian Kuupol demonstrates, had great significance in the worship of the gods.

Images of gods and goddesses were venerated with a kiss as the customary way of showing respect to the divine. Traditionally, the divinities could also be greeted with a kiss from a distance. Caecilius, a pagan, for instance, threw a kiss to the statue of Serapis when he saw it from a distance…Similarly, in the sacred scriptures of the Jews, Job protested his innocence of not throwing a kiss to the stars as a form of adoration.[4]

Kuupol’s last point is a reference to Job’s protest of his innocence in Job 31. Job paints a series of theoretical situations in the form of rhetorical questions that would establish his guilt, had he actually done these things. Job says:

24 “If I have put my trust in gold or said to pure gold, ‘You are my security,’ 25 if I have rejoiced over my great wealth, the fortune my hands had gained, 26 if I have regarded the sun in its radiance or the moon moving in splendor, 27 so that my heart was secretly enticed and my hand offered them a kiss of homage, 28 then these also would be sins to be judged, for I would have been unfaithful to God on high.

Had he thrown a kiss to the sun or moon, in other words, that would have been a blasphemous act and one rendering him unfaithful to God. But, Job says, he has not done such a thing.

A thrown kiss is a powerful thing, whether between human beings or as an act of religious devotion. One commentator writes that “it was usual to throw kisses to the sun and to the moon, as well as to the images of the gods, fearful of touching them with profane lips.”[5] Almost certainly, this is what Alexamenos is depicted as doing in this graffiti. In this, Alexamenos is shown to be involved in behavior that would certainly, on the face of it, have been familiar to any who saw the graffiti. As Raymond S. Perrin writes:

The life of the Greeks was a succession of religious ceremonies spontaneously mingled with every thing that they did. All their festivals were religious; they prayed for every thing that they wanted in a loud voice with their hands extended toward heaven, and they even threw kisses to the gods.[6]

But, upon viewing this otherwise familiar scene, the Roman viewer would have been struck, first, with horror, and, then, with scorn at the object of Alexamenos’ worship: the donkey-headed god on the cross. Thus, Alexamenos’ act of adoration was rendered absurd by its object.

Keegan offers a helpful summary:

…Christians, as well as non-Christians, worshipped with arms extended and raised, while here we see the left arm lowered and the right extended towards the figure on the cross with the fingers open and separate in the Roman manner of iactare basia. If we allow for the probability that a young slave named Alexamenos worshipped the Christian god in the Palatine Paedagogium, then the graffitist who scratched this inscription was most likely ridiculing the act of prayer itself.[7]

Iactare basia comes from the Latin word “iacto” (to throw) and “basium” (kiss).

Here, the question of whether Alexamenos is throwing his left hand or his right hand brings a bit of nuance to our understanding of the graffiti. Harley-McGowan believes we are seeing Alexamenos “in strict frontality” and, as such, it is the left hand that is being thrown while he looks up and to the left.[8] Oliver Larry Yarbrough, however, argues that “the right arm is extended upward toward the central figure and is bent at the elbow; the curved left arm is extended downward and away from the body.”[9] This would mean we are seeing Alexamenos’ back with his head turned to the right.

Frankly, the joke works either way. If we are seeing his back and he is throwing his right hand with his head turned up and to the right, then he is using the method that Romans would have used. The joke, then, would be in the juxtaposition of the respectful sign that they understood and the absurd object of Alexamenos’ affection (Jesus on the cross) that they most certainly did not understand. If we are seeing the front of Alexamenos and he is throwing his left hand with his face turned to the left, then the joke is heightened by the fact that not only is the object of his devotion unfit for such honor but Alexamenos’ foolishness has rendered him unable even to throw the kiss rightly.

Either way, Alexamenos’ fellow students would have found this hysterical.

Demonstrative Worship

We are, of course, interpreting this graffiti. Yet, based on the best evidence, it is reasonable to say that what makes the graffiti funny to Alexamenos’ peers is the object of his worship (or prayer). The youth of the paedagogium who were deriding Alexamenos found the idea of worshiping a donkey-headed deity obscene and absurd.

What strikes me, however, is that Alexamenos worships Jesus. His devotion was genuine, sincere, and, presumably, passionate. That is how he is depicted in the graffiti with his gaze and with iactare basia, the throwing of the kiss of reverence.

The rub for the graffiti artist was Alexamenos’ sincerity. It is as if he is saying, “This guy actually believes in this stuff!”’ In Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut says of the character Billy that he “had a meek faith in a loving Jesus which most soldiers found putrid.”[10] Likely the same dynamic was at play here. But the sincerity of Alexamenos is what makes this image so very powerful for believers today. We view this and ask, “Do I really believe this stuff? Is my worship sincere?”

Alexamenos stares upward at Christ and raises his hand in adoration. There was intentionality to his worship, deliberateness, focus. Even if such actions had not been observed by the bullies of the paedagogium, this was the alleged and mocked state of Alexamenos’ posture toward this crucified Christ: adoration. And there is nothing to suggest that the depiction of the young man was inaccurate.

Here, again, a cultural difference: Alexamenos was mocked for his sincerity in worship, but a mocking graffiti of Christians in the West today would likely highlight our hypocrisy, our betrayal of Christ, our failure to worship, our lack of adoratio.

J. Budziszewski writes:

Contemporary American pop spirituality is a theology of lingering, of loitering, of hesitation, a religion of the vestibule. It wants connectedness without commitment, reconciliation without repentance, and sacredness without sanctity. It wants to sing the songs of Zion in the temples of Ishtar and Brahman. God help us to know what we want and to want what we ought.[11]

Here is how Calvin Miller captured much of what passes for devotion in contemporary American Christianity.

I’m but a cash-card saint in celluloid.

Can I afford to call this Jesus, King?

I’d like to follow him and yet avoid

Cross lugging and a naked death. I sing

Therefore to harmonize and think of all

I’ll eat when singing’s over with. Born twice,

By hundreds, then, we gather at the mall

And bless the church, or clap, or criticize.

Grace by installment - total faith - and we

Can spot a bargain when there’s one in town -

The maximum of everything that’s free -

With nothing but the minimum paid down.

It makes his love so interest-free! Not hard!

Like taking up your cross by Mastercard.[12]

Is there enough of the kind of devotion detected by Alexamenos’ unsympathetic peers in us to warrant such a graffiti? Is there enough adoratio within us to earn us a good bullying? Whatever else might be said about those cruel scratchings in that wall, they are, from the Christian vantagepoint, a compliment. For us, Alexamenos’ sincerity should be a goal. W.A. Sessions, in his introduction to Flannery O'Connor's prayer journal, referred to "her outlandish hope, at least in the twentieth century, for total commitment to God."[13]

Alexamenos embodied that “outlandish hope.” As depicted in the graffiti, Jesus was His great treasure. I marvel at that. His “friends” found it hysterical.

This would not be the last time that those outside the church found the devotion of the young to Jesus worthy of comment. Some years back, Rolling Stone magazine reporter Stephanie Keith posted a photojournalism report of her investigation of the Contemporary Christian Music scene. She went to concerts and churches and observed the phenomenon of Christian rock music and the (mostly) teenagers who listen to it. Her report was entitled, “Young and Pious: A Rock & Roll Story.” It consists of twelve photographs from various Christian venues showing teenagers in various states of excitement, religious rapture, and euphoria during Christian rock concerts. There are pictures of Christian teens praying, swooning, shouting, staring blankly at the camera, etc. And, beneath these twelve pictures, Stephanie Keith, the reporter, wrote her brief reflections on what she saw and witnessed at these events.

Her comments are interesting. Some of what she saw does indeed sound strange. She seems, by and large, confused at this wedding of Christian lyrics and rock music. She seems, at times, amused at the Christian subculture of teens who flock to Christian rock concerts.

Maybe her most interesting comment comes at the end of her report. It’s posted under a picture of a teenage boy who seems caught up in the moment and the music at Virginia's Acquire the Fire event, which was held on January 30th, 2003. The teenage boy’s eyes are closed, his arms bent upward in a posture of reception, maybe of prayer. And beneath this picture, Stephanie Keith placed this comment: "Jesus is their personal savior. He's almost alive to them."[14]

“He’s almost alive to them.”

Almost?

For followers of Jesus, He must certainly is alive. And this drives our worship, or it certainly should. For Alexamenos, it did.

Were our worship and devotion depicted artistically, what would it look like? What would be said about us: “Jesus is almost alive to them”? “Jesus actually appears to be dead to them”? “They appear to be indifferent to the Jesus they profess”? Would the image match our calling to love the Lord and worship Him? Or would we have a Dorian Gray moment with the image depicting a more sinister and pitiful reality than what we project when others are around?

With Alexamenos, there is no question. We see him as the other boys saw him: face turned up to Jesus, eyes focused, the hand offering prayer and the kiss of adoration.

Alexamenos worships His god.

Do we?

[1] O'Connor, Flannery. A Prayer Journal. (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), 35.

[2] Those who think we are seeing the front of Alexamenos and he is throwing his left hand include Edward Charlton, who writes that Alexamenos “has not the hands outstretched, as was the custom of the early Christians when they prayed, but one hand, the right, is unemployed, and hangs by the side of the figure, while the other is outstretched towards the figure on the cross.” See also: “Roman Caricature of Christianity.” Archaeologia Aeliana. Volume V (Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: William Dodd, 1861) 200. So, too, Taylor, Archer. The Shanghai Gesture. (Finland: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia,1956) 8. Felicity Harley-McGown holds to the “left arm” position as well in “The Alexamenos Graffito.” In The Reception of Jesus in the First Three Centuries. Edited by Chris Keith, Helen Bond and Jens Schröter. Vol. III (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2019) 111. Oliver Larry Yarbrough (quoted and referenced above) is indicative of those who believe it is the right arm that is extended.

[3] Turcan, Robert. The Gods of Ancient Rome. Translated by Antonia Nevill. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2000) 4.

[4] Kuupol, Cyprian. Kyrie Eleison. (Xlibris, 2019).

[5] “Origin and History of Kissing.” Manford’s Magazine. XXXII.10 (October 1888) 585.

[6] Perrin, Raymond S. The Religion of Philosophy. (London: Williams and Norgate, 1885) 448.

[7] Quoted in “.” Demons in Early Judaism and Christianity. Edited by Hectore Patmore and Josef Lössl. (Leiden: Brill, 2022), 218.

[8] Harley-McGowan, Felicity. “The Alexamenos Graffito,” 109, 111.

[9] Yarbrough, Oliver Larry. “The Shadow of an Ass: On Reading the Alexamenos Graffito.” Text, Image, and Christians in the Graeco-Roman World. Edited by Aliou Cissé Niang and Carolyn Osiek. (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2012) 241.

[10] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five (RosettaBooks) Kindle Edition 38–39.

[11] Quoted in Neuhaus, Richard John. “While We’re at It.” First Things. January 1996.

[12] Miller, Calvin. The Unfinished Soul (Carol Stream, IL: H. Shaw Publishers, 1997) 76.

[13] O'Connor, Flannery. A Prayer Journal. (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013) xi.

[14] http://www.rollingstone.com/news/story/11365677/photo_gallery_teens_of_christian_rock/12

Brother Bryan of Birmingham & Alexamenos are beckoning me from the great cloud of witnesses this week.