Introduction / Alexamenos

How an 1800-year-old Anti-Christian Graffiti in Rome Can Teach us about Jesus and What it Means to Follow Him

What makes an image compelling, arresting, attention-grabbing? Why do some images stop us in our tracks but not others? Why is it that a person can point you to a picture or a painting or a drawing that has seemingly changed his or her life, yet you stare at it with confusion, wondering what exactly it is that the other has seen in it?

“Ferris Bueller’s Day Off”—the beloved 1986 John Hughes film about a charming and imminently-likeable slacker skipping a day of school and adventuring around Chicago with his girlfriend, Sloane, and his daddy-issues-laden friend Cameron—will seem like an odd place to begin a consideration of this question, but hear me out. There is a memorable scene in the movie that truly is both poignant and haunting.

The trio visits the Chicago Art Institute during their adventure in truancy. There, they gaze upon the priceless works of art together until Ferris and Sloane step away. We then find Cameron—neurotic, lonely, fearful, fragile, angry-at-his-father Cameron—standing alone before Georges Seurat's famous painting, "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte."

Cameron stares at the painting, but he is more than merely staring at it. He is transfixed. The camera cuts back and forth from Cameron’s face to the painting, drawing ever-closer to each.

We realize that Cameron is staring at one particular part of the painting: the little girl in the center, holding her mother’s hand. The little girl is staring out of the painting. Cameron is staring at her.

The camera moves closer to Cameron’s face, his eyes wide, seemingly stunned. Each shot of Cameron’s face seems to reveal increasing intensity, a growing sense of awareness coupled perhaps with something like dread.

Interspersed with these shots of Cameron’s face, the camera moves closer and closer to the little girl’s face until, ultimately, we are drawn into the distorted hyper-closeup of the fibers of the canvas itself.

This is haunting stuff. We are witnessing something powerful here. One gets the feeling in watching the scene that something possibly awful but also strangely beautiful is happening. It is a moment of devastating self-awareness on Cameron’s part. The little girl in the painting is communicating something to him. There is something almost sacred unfolding before our eyes.

What is it? What is happening? Why this moment of seeming existential reckoning on Cameron’s part?

When one learns about Seurat’s painting and what is likely happening in it, this scene becomes even more evocative, and we begin to approach a kind of understanding.

For instance, the location that Seurat painted, “La Grande Jatte,” is an island in the Seine River near Paris that, at that time, was notorious because it was frequented by prostitutes. This detail of location immediately belies the innocent view of people lounging, idyllically and lazily, beside the river and makes us a bit more guarded concerning who exactly is in this picture and what exactly is happening here. It also makes us look more closely at some of the odd details, like the lady holding the leash affixed to a monkey or the lady at the river who is fishing, a detail that many see as a metaphor for the unseemly transactions happening in that area.

Secondly, there is the fact that the little girl that Cameron is staring at is the only one in the image looking out, “breaking the fourth wall,” as we might say. She is viewing the viewer and only she is doing it. This gives us a heightened sense of isolation: the girl is in the crowd and is yet somehow detached from it, somehow a world unto herself, possibly even contra mundum, against the world.

Third, the little girl is given the greatest amount of light in the painting as well as a white garment. She is a picture of purity surrounded by shadow, by decadence, by baiting, by appetite, by averted glances.

Next, the one person on the canvas viewing the viewer is holding the hand, presumably, of her mother but most certainly not of her father. Her father is absent.

Seurat painted this painting using pointillism (“a highly systematic and scientific technique based on the hypothesis that closely positioned points of pure color mix together in the viewer’s eye” and “coalesce into solid and luminous forms when seen from a distance”[1]). This is why, the closer and closer the camera zooms in on the child, the more distorted the image becomes until, ultimately, you can tell that what you thought was a person is actually just a series of points, of dots.

Now, Cameron’s reaction to the child in the painting becomes clearer. A child, surrounded by people but oddly alone, innocent though in an environment of infamous impurity, absent her father, stares out at Cameron who, in his peering, discovers that the closer and closer you get to the child the more and more her humanity, her personhood, dissipates and disappears. He sees himself in the child—without his father, surrounded by a dark and foreboding world, alone, and haunted by a singular question: When one looks closer and closer at Cameron, is there really even a person there at all?

This scene in the movie lasts less than one minute, but it is mesmerizing and memorable. The added details of the image itself positively galvanizes it into the viewer’s consciousness.

Can one lose one’s way in this kind of analysis? To be sure! Perhaps we have even done so here, though the fact that Seurat was offering social commentary through this image seems fairly settled.

There is an orbit to images, a gravitational pull. Cameron could no more have wrested himself from that moment than any other imprisoned person can from their own cell. Something there caught not only his eye but his soul. He was, again, transfixed.

There is a world within images. Each painting is a cosmos. Each drawing is a universe. We find some of these universes compelling, some of them revolting, and, about others, we are almost completely indifferent. Is it not so? Why is one person moved to tears or dread or anger or peace by an image while the person next to them shrugs and moves on? Perhaps we call those works of art “great” that just so happen to move more people on a deep level than is usual.

The Graffito Blasfemo

I would like to invite you to stand before an image, to enter a particular image’s orbit, to enter its world.

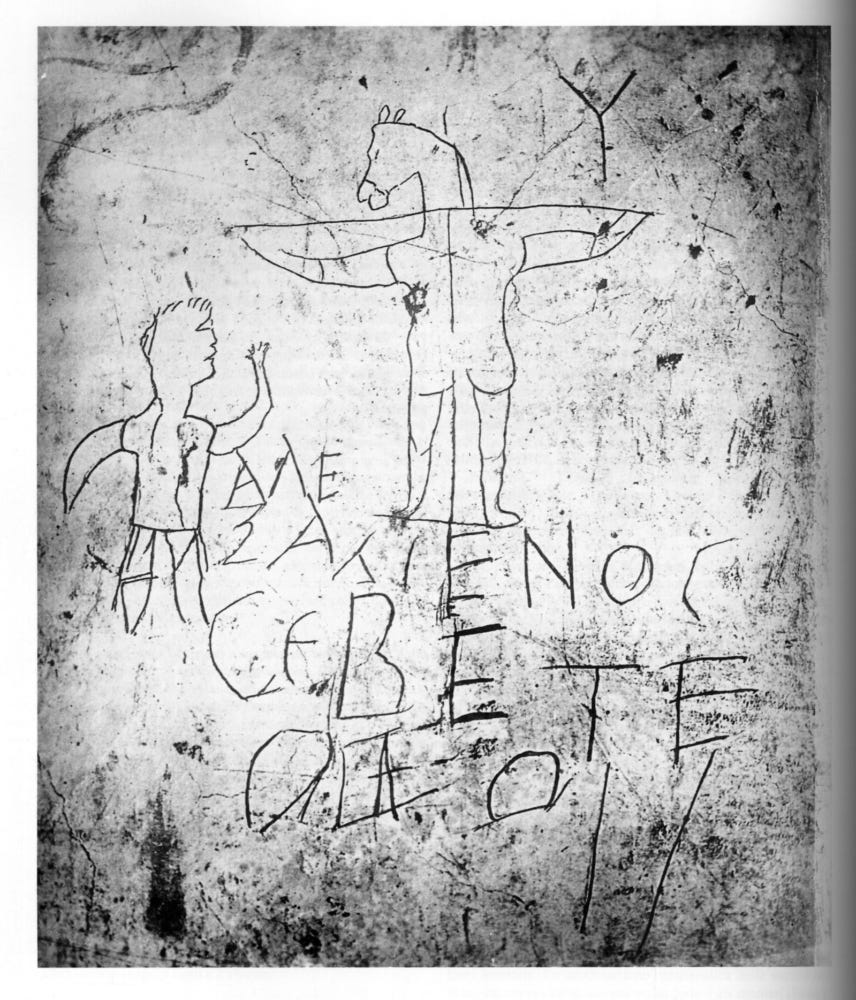

There is an image from around eighteen-hundred years ago that has a strangely powerful gravitational pull. It is graffiti, scratched into the wall of a kind of school in Rome around the end of the 2nd century or beginning of the 3rd. It too has curious elements. It too asks the viewer certain penetrating questions. It too is a universe. It too beckons us in. And it too involves a young person surrounded by powerful realities that call for our interpretation and our consideration.

But in this graffiti—unlike the little girl in Suerat’s painting—the young person depicted therein is not staring at us, but at somebody else. And that “somebody else” is depicted in the strangest of ways.

There is something unsettling about this graffiti.

There is something troubling about this graffiti.

There is something upsetting about this graffiti.

But, strangely, paradoxically, surprisingly, there is something beautiful and inspiring here as well.

To get at this we will need to draw closer and closer to this image and, as much as we can, step into the world of it.

Perhaps you will find yourself transfixed. Perhaps you will find yourself repulsed. I rather doubt you will find yourself indifferent.

I invite you to stand with me before the Alexamenos Graffito.

[1] https://www.artic.edu/artworks/27992/a-sunday-on-la-grande-jatte-1884