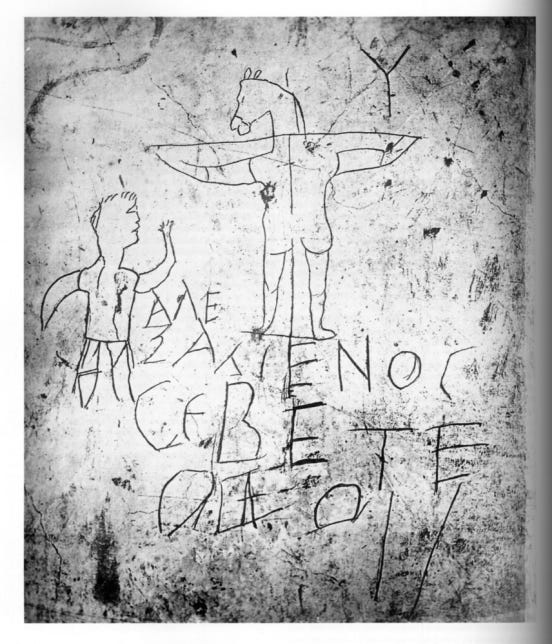

Chapter 6, "Colobium" / Alexamenos

How an 1800-year-old Anti-Christian Graffiti in Rome Can Teach us about Jesus and What it Means to Follow Him

[Want to get caught up? Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, chapter 5]

“The Alexamenos inscription, therefore, is not just about a child’s religious allegiances; it is also about his social status and the precariousness of his existence.”

Candida Moss, God’s Ghostwriters, 2024

“Numerous and indistinct, as a group, slaves were the least identifiable and the least noticed among the Roman population; possessing no identity of their own separate from their master, they had no public ‘self’ of their own to assert through clothing.”[1]

Michele George, “Slave Disguises in Ancient Rome,” 2002

I know the names of my ancestors’ slaves. How many people can say that?

The last will and testament of Revolutionary War Brigadier General Richard Richardson was signed in 1780, the year he died. I stand in direct paternal lineage to Richard Richardson. He is truly my Grandfather, times about 6. There’s a monument to him on the statehouse grounds in Columbia, SC, 2 or 3 miles from where I was born at Richland Memorial Hospital. Main Street in Columbia used to be called Richardson Street after my Grandfather. Every now and again, when we return to my hometown, some of us will drive out to Rimini (about 25 minutes from my parents’ house but less than ten miles from the old homes of my immediate grandparents, all of whom have passed on), and see his tomb there on the grounds where the grand old Richardson house once stood: Big Home Plantation, as it was known.

And when we go we also look over at the grave of General Richardson’s beloved horse Snowdrop. Richard Richardson put up a stone for his horse.

I am in many ways proud of my Grandfather. He fought for the patriot cause of freedom and led the Snow Campaign to squelch the loyalist cause in the backcountry of South Carolina. The legend is that the British Col. Tarleton had my Grandfather’s sons exhume his body from the grave so that he could see, he said, the man who had eluded him for so long. I like these stories. I like the romance and legend and history of these stories. I realize that in many ways my life is better because of the actions of Richard Richardson.

And yet…

He fought for freedom, but he owned slaves. This, I am not proud of.

I do not know where their headstones are. Were any put up? I know where his horse is buried. I do not know where his slaves are buried. But I know their names. They are listed in his last will and testament as follows:

IN PRIMUS, I give and bequeath to my well beloved wife, Dorothy Richardson, the thirty-four following Slaves or Negroes (vis) Tom the Carpenter, Judy, Ned & Agar, his wife & 2 children, Tommy, Thisby, Tommy & Fally, Devonshire, Nanny, Paul, Qui, London, Silcey, Moses, Fam, Tohan, Kate, Peter, Peggy, Jack, Pollipus, Balliss, Billy, Stump, Phebe, Gabriel, Phebe, Rachel, John, Priscilla, Fusy, Judah, Balina with their and each of their Issue & Increase…

And later:

I give and bequeath to my beloved daughter, Susannah, my beloved sons—James Burchell, John Peter, Charles and Thomas Richardson, ten Negroes each, to be of equal value and worth with the use given to my other children, and the remaining part of my Negroes to be equally divided between my nine children and that my beloved daughter, Susannah, have the following ten Negroes, being the Tenth part allotted as above (viz) Sarah, Cyrus, Peter, Juky, Jefe, Hancel, Nill Beck, Home, Toby and Jack’s Creek Betty with their future Increase.

And, again, later:

I give and bequeath the rest and residue of my lands to my beloved sons, John Peter, Charles, and Thomas Richardson, to be divided in equal valuation between them, unless my wife should prove pregnant, in such case (if it should prove a Son) then he shall be entitled to an equal part of lands with the three last mentioned and ten Negroes & an equal part of the Surplus…

And, again, later, near the end of the will, because he apparently forgot, he came back around to what he bequeathed his wife, Dorothy, my grandmother:

I give and bequeath to my dearly beloved wife, Dorothy Richardson, one more Slave, named Mulattoe Bob, the weaver, besides those before mentioned…

And there it is. Doled out alongside his featherbeds and sword and buckles and horses and land are his slaves. Handed out. Divvied up. And I ask myself this: If my Great Grandfather’s actions against the loyalists shaped my life for the positive did my Great Grandfather’s actions against Judy, Ned & Agar, his wife & 2 children, Tommy, Thisby, Tommy and Fally, Devonshire, Nanny, Paul, Qui, London, Silcey, Moses, Fam, Tohan, Kate, Peter, Peggy, Jack, Pollipus, Balliss, Billy, Stump, Phebe, Gabriel, Phebe, Rachel, John, Priscilla, Fusy, Judah, Balina, Sarah, Cyrus, Peter, Juky, Jefe, Hancel, Nill Beck, Home, Toby and Jack’s Creek Betty with their future Increase, and “Mulattoe Bob” shape my life for the negative?

I once shared this information on a blog I ran. It was noticed by somebody. This person saw his Grandmother’s name in the list of my Grandfather’s slaves. He thanked me for the post. He wanted to know if I had any information on where my Grandfather buried his slaves. With sadness, I explained that I did not, and we discussed possible avenues of research.

This bothered me.

Among the many tragedies surrounding this odious commerce stands the dehumanization of the slave. The singular name. The occasional added name shaped by the slave’s utility: Bob the weaver, for instance. The non-prominence and forgettability of the slave cemetery.

I hope and pray that this dear person can find where his Grandmother was buried. He should know. We should all know. But he knows her name. If nothing else, there is that. And that is no small thing.

One way that slaves in Rome (and elsewhere) were dehumanized or, at the least, that their low station in life was highlighted was through simple, course, functional dress. This was deliberate. “The Romans were very sensitive to distinctions of dress and the symbolic associations of costume,” writes Keith Bradley.[2] This sensitivity can be seen in the artistic decisions behind the depiction of Alexamenos.

The image depicts Alexamenos as wearing the Roman colobium. This was the garment of the slave: a simple, short, tunic, either sleeveless or with very short sleeves.

Joseph Strutt speaks further to Roman slave dress.

The slaves in Rome wore habits nearly resembling the poor people; their dress, which was always of a darkish colour, consisted of the exomis, or sleeveless tunic, or the lacerna, with a hood of course cloth; they wore the crepidae for their shoes; and their hair and their beards were permitted to grow to a great length.[3]

John Stambaugh observes that

The coarse brown wool that slaves in Rome wore came from Canusium, in southern Italy…and cheap woolen blankets and tunics were imported from Gaul. Sources of still cheaper clothing were the cenonarii (“rag pickers”), who gathered up worn garments, recycling what was usable into patchwork tunics, blankets, and saddle cloths…[4]

The descriptive language employed by Strutt and Stambaugh help us get a sense of the quality of slave attire: “resembling the poor people,” “course cloth,” “coarse brown wool,” “cheap,” “cheaper clothing,” “worn garments,” “patchwork tunics.”

Moss on Slavery

Candida Moss has offered a most helpful consideration of the possible social status of Alexamenos in her book, God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible. She observes, for instance, that Alexamenos and his fellow students were likely “enslaved members of the imperial family” and that the paedagogium “was in truth more a workshop than a school” where “the students were shaped into copyists, bookkeepers, and secretaries.”[5]

Moss highlights the dangerous situation of the Roman slave. “Shadowlike, the threat of violence followed them throughout the day, only partly receding in the quiet darkness when everyone was asleep.”[6] Were he or his parents brought to Rome as slaves from elsewhere, Moss informs us, they would have passed through the dehumanizing slave markets and subjected to “a battery of intrusive tests”: “eyes were poked, limbs raised and lowered, orifices probed and fumigated, breasts and abdomens palpated.”[7]

Roman slavery was not about race, writes Moss. It was rather about otherness, about the traits of ethnic identity: “language, religious customs, diet, dress, kinship, homeland, burial traditions, and sometimes blood.”[8] In other words:

It’s possible…that Alexamenos was doubly marked both as enslaved and as belonging to a specific ethnos or people. If so, being a foreigner with strange religious interests would only have amplified his liminal status in the classroom. More probable, however, was that Alexamenos was what Romans called a verna, or home-born slave. Chilling theories of “slave management” espoused the advantages of home-born workers to their enslavers. The home-born could, like all children, be shaped and controlled from infancy and used as a hostage to ensure the loyalty of their biological parents.[9]

If this is so, Alexamenos would have had the most fragile and tenuous of connections to his own parents, possibly possessing only “a bond that lived in glances, small gestures of support and protection, and brief moments of intimacy.”[10]

There were other dangers, horrific in their details. Moss notes that if Alexamenos “were deemed beautiful…he might have been a delicatus, an ‘exquisite’ boy who was a sexual plaything for a predatory male householder.”[11]

The delicati were not only sexually abused, they were occasionally forcibly castrated to preserve their youth and looks. Out of desperation, some enslaved workers used their meager peculium—an ephemeral “salary” that could evaporate at any time—to purchase ointments that promised to hasten puberty. They didn’t work.[12]

Moss goes on to write of a litany of dangers associated with being an enslaved person in Rome. Her language and terminology on this front paints a most unsettling picture of what life was like for Alexamenos and other sin his station: “omnipresent violence,” “beatings,” “exceptional cruelty,” “internal scars,” “emotional labor,” “relentless” fear, “despotic enculturation,” etc.

This was the world of Alexamenos.

The existential chasm between the experience of a Roman slave and many (though not all!) people today demands an unflinching look at the horrors of subjugation. We will be tempted to avert our eyes, even our sympathetic consideration of Alexamenos. We must not. Let us be sure of this: That graffiti—while experientially unpleasant—was, in some ways, the least of his worries.

Seeing the Unseen

The colobium was not only a marker of a degraded social status, it was also a symbol and commentary on the slave. The tunic was simple, coarse, unadorned, functional, and lacking in any flourishes.

There can be no doubt that had a student in the paedagogium said to Alexamenos, “Hey, Alex! Two thousand years from now, people will be discussing you and your faith. People will know your name. You will be written about!” that it would have been seen as yet another expression of mockery.

The slave was a tool, not a person.

His presence was registered, but not seen.

But we see him. We see Alexamenos. And, above all other names scratched in the wall of that paedagogium, he is remembered.

The colobium that Alexamenos wears therefore makes our remembrance of him all the more amazing, miraculous even. The colobium spoke of insignificance, of dehumanization, of obscurity. Yet the slave boy, Alexamenos, is not only remembered, he is actually being studied, here, now, by you and by me. More than that, we are looking to him as a model in this book, as an example. This means something really quite astonishing has happened: We are being led by a slave!

It is only in the context of the church that something like this could happen: that the insignificant could become the model, that the discardable could become the prized. Everything about slavery screams, “Irrelevant! Ultimately unimportant! A tool to be used and thrown away!” But in the context of a gospel community, the slave has these markers of degradation removed and, through Jesus, significance and worth is conferred.

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. (Genesis 1:27)

The imago Dei, the image of God, is imprinted upon all human beings, and this is a prioritized image. Try as the world might to call a human being an animal or a tool or a waste of flesh, the Lord God calls us men and women, image bearers.

I was privileged in my doctoral studies to take a course on preaching with the esteemed African American homiletician, James Earl Massey. Dr. Massey spoke frequently of his affection for Howard Thurman. Massey has passed along this moving insight from Thurman.

Howard Thurman writes about how impressed his grandmother was with the preaching that she, a former slave, had heard from a certain slave preacher when she was a girl. That slave preacher had drilled into the consciousness of his Black hearers the notion that they did not have to feel inferior because they were enslaved. Thurman writes, “How everything in me quivered with the pulsing tremor of raw energy when, in her recital, she would come to the triumphant climax of the minister: ‘You are not niggers. You—you are not slaves. You are God’s children.’ This established for them the ground of personal dignity.” And out of that profound sense of being children of God, those slaves could handle the pressures of their days.[13]

I know not if this sentiment was communicated to Alexamenos around the year 200 AD in language fitting for him, but it is an astonishing privilege to be able to say it to him now. So, if you will allow me a moment of creative license, of retroactive encouragement, I would like to say:

You are more than the colobium you wear, Alexamenos. You are more than the paedagogium you inhabit. You are more than the graffiti that mocks you. You are, in fact, a human being, created in the image of God, and the special object of God’s affection. You are beloved by God. You are beloved by the church, the body of Christ, the one to whom you looked and the one that looks at you. You are not a tool, a beast of burden, a means to the end of the powerful in Rome. You are not the punchline of a joke. You are not forgotten, unknown, unseen, and unappreciated. You are part of the cloud of witnesses. You are loved, Alexamenos, and you have shown us a glimpse of what it is to follow Jesus. And you are remembered. And now you are home.

And I say the same to you, reader. You are not defined by the diminishing insults of the world. You are defined by what God says you are. You, too, bear His image. Christ has likewise died for you. You, too, are beloved.

You are not a slave. You are seen by the one with nail-pierced hands. And that changes everything!

[1] George, Michele. “Slave Disguises in Ancient Rome.” Representing the Body of the Slave. Edited by Thomas Wiedemann and Jane Gardner. (Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 2002) 51.

[2] Bradley, Keith. Slavery and Society at Rome. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002) 95.

[3] Strutt, Joseph. A Complete View of the Dress and Habits of the People of England from the Establishment of the Saxons in Britain to the Present Time. (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1842) cxiv.

[4] Stambaugh, John E. The Ancient Roman City. (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988) 151.

[5] Moss, Candida. God’s Ghostwriters. (New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company, 2024) 21.

[6] Ibid., 22.

[7] Ibid., 23.

[8] Ibid., 24.

[9] Ibid., 25.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., 28.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Massey, James Earl. Views from the Mountain: Select Writings of James Earl Massey (Aldersgate Press) Kindle Locations 711–17.

Great observations. Seems slavery is always with us and always essentially the same. From Rome to Rimini to today's misplaced children it's always about using someone else for our own purposes.