Chapter 7, "Imaginings, Part II" / Alexamenos

How an 1800-year-old Anti-Christian Graffiti in Rome Can Teach us about Jesus and What it Means to Follow Him

[Want to get caught up? Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, Chapter 5, Chapter 6]

In 1903, the Italian poet Giovanni Pascoli wrote his poem “Paedagogium.”[1] This Latin poem would win the prestigious Certamen poeticum Hoeufftianum award in 1904. Of the fictional imaginings of Alexamenos, this is one of particular power. When I first read it, I was so caught off guard by the ending that I found myself in tears at its beauty.

Pascoli correctly situates Alexamenos in the time of Lucius Septimius Severus, who was Emperor from 193–211 AD. The paedagogium is depicted as a place where “hostages” from Roman conquests were housed and where “free guardianship” was offered in particular to “those princes stolen from throughout Roman lands.” There, boys from around the world would learn their Latin letters and their games and so be enculturated in the ways of Rome.

Forgetting their fatherlands, hidden by those clouds or smoke, or lying wild below the eastern sun, the lads played: the Irishboy sent a ball, the Arab accepted; the throwing collapsed the Briton’s castles which the African constructed with nutshells.

In the midst of one such game, one boy, Kareius by name, calls out to another.

“Hey, you!” the rusty-haired boy called out to the lad with the black locks. “You Syrian or Aramaean or-”

“My name is Alexamenos.”

He wants Alexamenos to join in their game, but Alexamenos does not want to. He says, instead, that he needs to learn the lines that he will soon have to recite aloud. Kareius is not pleased.

“Put down the booklet, munched by moths, and pick up our ball like you should.”

“Kareius, I’m a total newbie at that game.”

“Playing, as the wise man says, is the best teacher.”

“Actually, doing, not playing, I think, if you remember.”

For Pascoli, the seeds of tension are sown by Alexamenos’ studiousness and inability to hold his tongue and not correct others. Already we can tell this is heading toward a conflict. What is more, Pascoli depicts Alexamenos as looking different as well.

He was a different shade than his comrade in respect to all bodily parts, as well as in his face and voice, slender-framed, his cheeks suffused with sallow olive.

Alexamenos intimates that he does not want to get in trouble with their teacher by being unprepared, to which Kareius now introduces a religious dynamic to his growing irritation. Speaking first of the assumed religious views of their teacher, Kareius then insinuates that Alexamenos is a Christian, making reference to the slur that the Christians worshiped a donkey-headed god. The language is compelling here and paints a helpful picture of how a Roman young man might indeed have spoken of the Christians. Alexamenos tries his best to sidestep the insults that follow.

“You kiss up to that donkeyette, so he won’t be sad.”

“Stop it! The teacher is calling us, as he’s allowed to.”

“Actually, he oughta be called a tormentor.”

“But he’s pious.”

“If the wicked cross helps, use it.”

“What’s that?”

“There are people who love the cross.”

“What, really?”

“It stands so that you can worship that foul cow, like those weirdos, munching on bread mixed with blood. Why are you always avoiding us? Why do you mutter? Why shun the other boys, your playmates? I don’t want to believe it, but it’s because you recite your poetry to that ridiculous guy, Christ.” Then there he turned over the ball with both hands, and said: “What? Are you playing or not?”

Here we see the Roman revulsion of the cross, their low opinion of the strange Christians (“…like those weirdos”), their misunderstanding and disdain for the Christian observance of communion (“…munching on bread mixed with blood”), their separatism (“Why do you always avoid us?”), their dismissal of Christian prayer (“Why do you mutter?”), and, above all, their abhorrence of the Christian worship of Jesus (“I don’t want to believe it, but it’s because you recite your poetry to that ridiculous guy, Christ.”). In depicting Alexamenos’ situation in this way, Pascoli very effectively lays the foundation for the social ostracization that Christians might experience in Roman society.

Alexamenos is stung by Kareius’ words. Then, an eruption. Alexamenos knocks the ball from his hands and lunges at Kareius. However, it is over before it begins as one of the other boys strikes Kareius for his cruelty to Alexamenos “and compels the struggling child into the neighboring room.”

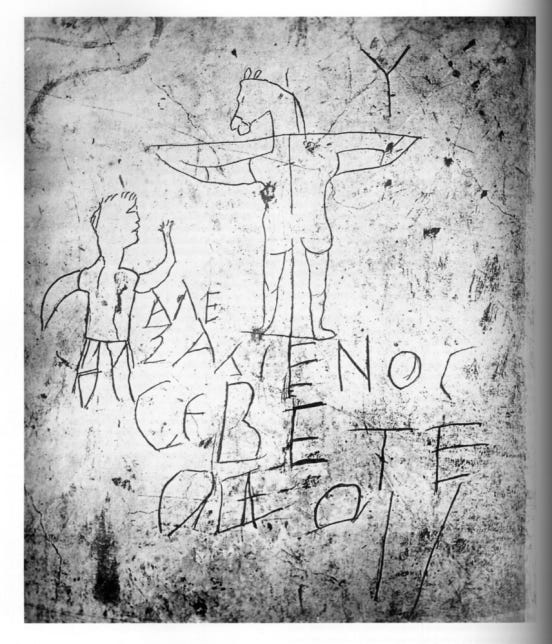

And it is here, sulking and furious in this “neighboring room,” that Kareius carves the famous graffiti.

Here the lad pounds the door and ground with his hands and feet. He continues to both tear at his cheeks and pull his red hair. Now shrieking mindlessly the horrible boy threatens many things, now, unavenged, he sighed submissively. Hating the other lad he suffers his punishment and fumes. Meanwhile, with an unsatisfying sob, silent in respect to his pencil and full of foreboding, he remained stuck where he pressed with his feet. Look, he seizes the pencil! Look, he inscribes the bitter wall! A cross appears from the double wound of the wall. A human body is affixed in a cross, wide with unfolded elbows, and a horizontal line supports the feet.

Then the neck and floppy-eared head of an ass were attached to the person. Now the eyes of the scribbler don’t swell with tears. Then he draws a boy standing and offering kisses or, by his left hand, incense to the animal affixed on the post. Now Kareius doesn’t sob. He said, “Who can deny this seems to be the devout and decent dude himself? But it helps to carve the name, so nobody doubts the figure’s identity. I’ll use Greek words and marks. Here slipping is permitted. That fowler won’t hunt for a single mistake, whatever it might be.”

Then, freed from the gloomy cloud, he wrote ‘ΑΛΕΞΑΜΕΝΟΣ ΣΕΒΕΤΕ ΘΕΟΝ’ and applauded himself.

Following this, Kareius calms himself as night falls. He is released and goes to bed where he begins to grieve under the terrible weight of his own homesickness. Then, Kareius notices something. It is Alexamenos, kneeling, praying.

While the sleepless boy mused to himself about these matters, he noticed another youth nearby was awake and moving. He listens attentively. He slips gently from the bed. His knees touch the ground, since in the darkness he’s suited to believe. Kareius understands Alexamenos. “What hurts him?” he asks, “And which god does he see in the darkness? What does he ask and pray for?”

“O FATHER,” that whisper begins to reveal itself to the tender lad. “WHO ART IN HEAVEN.” Night absorbs the rest and, in a confused murmur, words pierce the waiting ear.

Moved, Kareius asks Alexamenos to forgive him his cruelty from earlier in the day. Alexamenos forgives him and says of himself, “I should have put up with my classmate and been kind to a suffering person.”

The boys are reconciled.

Kareius asks Alexamenos why it is that he, Alexamenos, seems less agitated and less angry than Kareius when both of them have been torn from their parents. A beautiful conversation ensues.

“But my faithful mom gave me that place where I may be able to see and hug her again at a certain time.”

“What place?”

“Heaven.”

“Who will be your boss there?”

“God.”

“That guy you were just asking for something, whom neither of us can see?”

“He’ll see both of us.”

Kareius is moved, but still confused at Alexamenos’ commitment to Christian truth.

“Why do you always go on about these grand things, buddy?”

“Hugging me for the last time on the shore Mother ordered me to deny nothing, to betray nothing willingly.”

In the hands of Pascoli the poet, the conversation between the boys continues is a manner sweet and touching.

Both boys began to placidly go to sleep, having fallen silent for a long while, when in a soft voice the Gaul said: “Why do you often call me ‘brother’?”

“God is the one father of all of us.”

“The God that lives in heaven?”

“And by this king you may rise up and, at last, live again.”

“And I’ll be able to see Mom.”

The next morning, the teacher calls Alexamenos to the front of the class with all the boys present. He alludes to “an unconfirmed rumor” about Alexamenos (i.e., that he is a Christian) and then references the graffiti itself: “The rumor has spread about: even the walls themselves say it now.”

The teacher then mocks the idea of Christianity: that Christ is “a cow,” that the cross is fit for reverence (i.e., “Ravens have the right to honor a cross.”), and that only the Emperor is worthy of his allegiances. The teacher then makes a blunt demand followed by a beautiful expression of faith by Alexamenos.

“Now speak against Christ.”

“I praise him.”

“Wretched lad, you know the law.”

“Christ, Lord God, is my law.”

The teacher, disgusted and outraged, demands that Alexamenos get and stay away from the rest of the boys, proclaiming that his boys will not be stained by Alexamenos’ mad beliefs about Jesus. When he does so, however, an unexpected voice rises from the crowd, and the poem ends in a movement that is both wonderful and beautiful.

“Get away from those pure boys. Come. My group will be safe. Come away with your pestilence, while you’re still the only one carrying that disease.”

“You’re wrong: see, here’s another,” Kareius exclaims and offers himself to his brother, joining himself with a clasped hand to the boy who was leaving.

Giovanni Pascoli, in a surprising redemptive turn, depicts the graffiti artist, Kareius, as choosing to stand boldly with Alexamenos before the opprobrium of both the paedagogium teacher and the other students.

“Ecce alium,” the Latin original says. “Here’s another.” That is, “I too am now a Christian.”

In imagining the scenario in this way, Pascoli presents the graffiti as a moment of temporary anger that gave way before the overwhelming power of Alexamenos’ own witness and example. In a way both surprising and deeply moving, Pascoli turns the blasfemo into an occasion for further boldness, worship, and joy.

We are therefore invited by the poet to do the same.

[1] https://www.picciolettabarca.com/posts/paedagogium-by-giovanni-pascoli